"People say life starts from zero in America, but in my opinion, life here starts from minus." His words puzzled me at first, but as he explained, they began to make sense. "Honestly," he continued, "if you have to forget everything you knew before, isn’t life starting from minus?" It was a sobering thought—the realization that the American dream wasn’t just about starting over; it was about erasing the past, about becoming someone new in a place that demanded everything from you, even your memories.

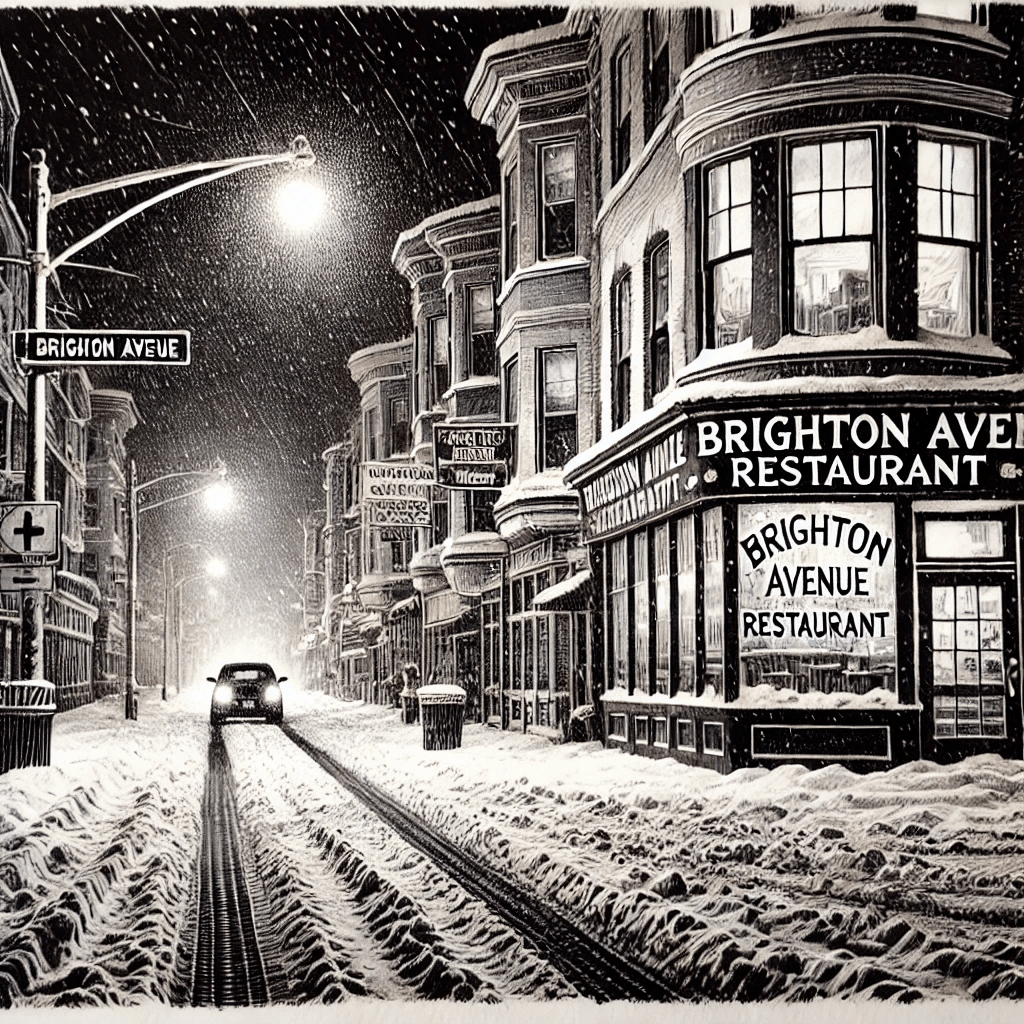

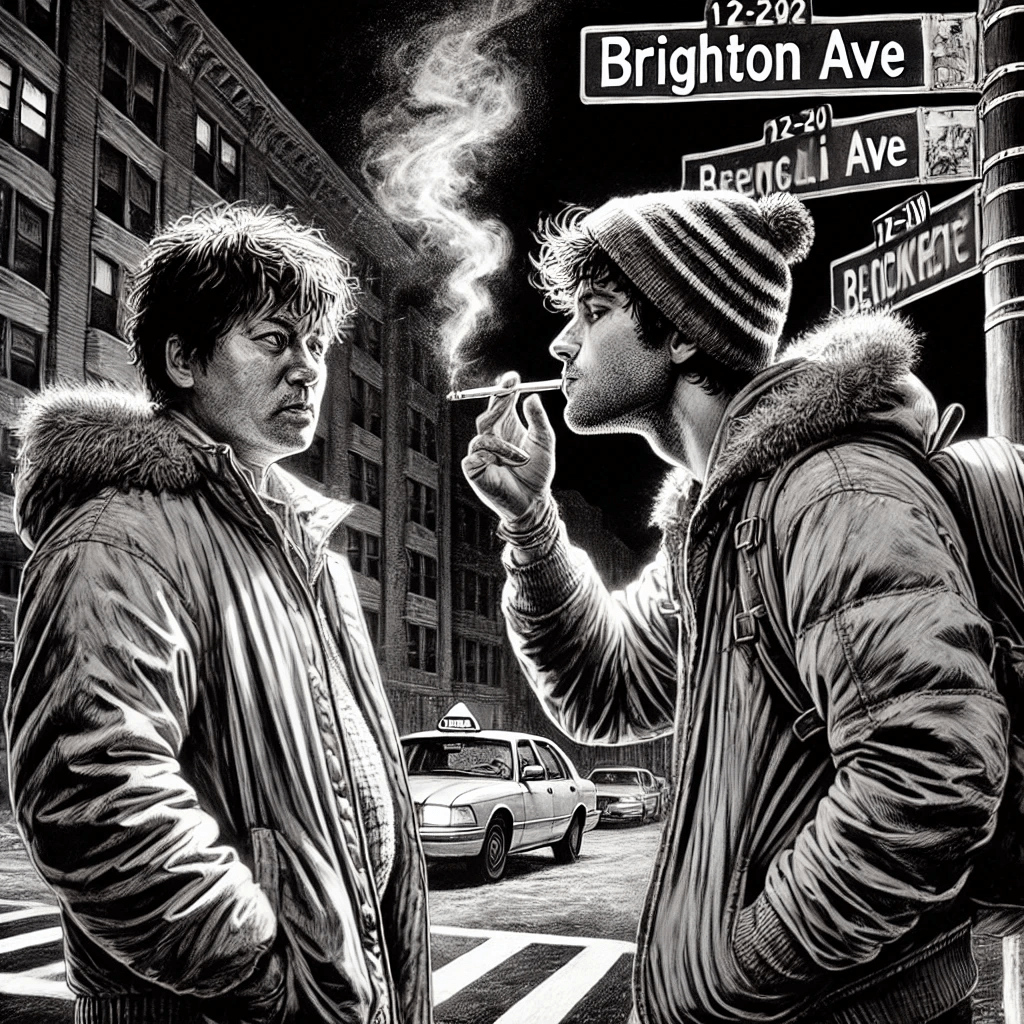

Winter’s bite was sharp and unrelenting. Each breath became a visible cloud, a stark reminder that home was a world away. Two months had passed since my arrival in America from Nepal, but it felt like an eternity. The year was 2013. The bright promise of the American dream, once so vivid, was now dulled by the harsh chill of reality. I wandered down Brighton Avenue with my friend Anil (name changed), who had arrived just two months before me. The streets, lined with the remnants of last night’s snowfall, had turned into dirty slush beneath our worn shoes.

As we walked, Anil turned to me, his breath hanging in the cold air like smoke. “Ram, you know, the job I’m doing now is actually my second one. Did I ever tell you that?” His tone was casual, but I could sense the unease beneath it. “I quit the first one just a few days after starting. But there’s plenty of work around here, so don’t worry. No need to panic.”

I nodded, though the truth weighed heavily on my chest. I had also found a job shortly after arriving—a position at a small grocery store, the kind with cramped aisles and humming fluorescent lights. But on the third day, the store owner fired me. Perhaps he saw something in me that I hadn’t yet recognized—a man struggling to keep pace in a world that moved too fast. “Don’t come to work tomorrow. I’ve decided not to hire any new workers right now,” the owner had said, his voice as flat as the bills he counted each night.

Anil and I had once spoken with such ambition, back when the idea of America was still a shining beacon on the horizon. But now, our conversations were tinged with the bitterness of unspoken failures. We no longer shared openly, reluctant to admit that the road to success was paved with more missteps than milestones.

The money I had brought from home was dwindling, each dollar spent a reminder of the urgency to find work. “Should we try here?” Anil asked, pointing to a nearby restaurant as we passed. It was an Indian restaurant, the scent of spices wafting into the cold air, reminding me of home in a way that made my stomach ache with both hunger and homesickness. “This is the place I mentioned earlier, where I worked for a bit,” Anil said as we reached the door.

“Oh, how long did you work here?” I asked, trying to gauge whether this could be a place where I might finally gain some footing.

“Four days,” he replied, and we stood there for a moment, the decision hanging between us like a curtain drawn against the cold.

Without warning, Anil nudged me through the door, staying outside where he couldn’t be seen from inside. The warmth of the restaurant enveloped me, and I found myself standing at the counter, face-to-face with a man who radiated cheerfulness. “Are you hiring?” I blurted out, the words escaping before I could think them through.

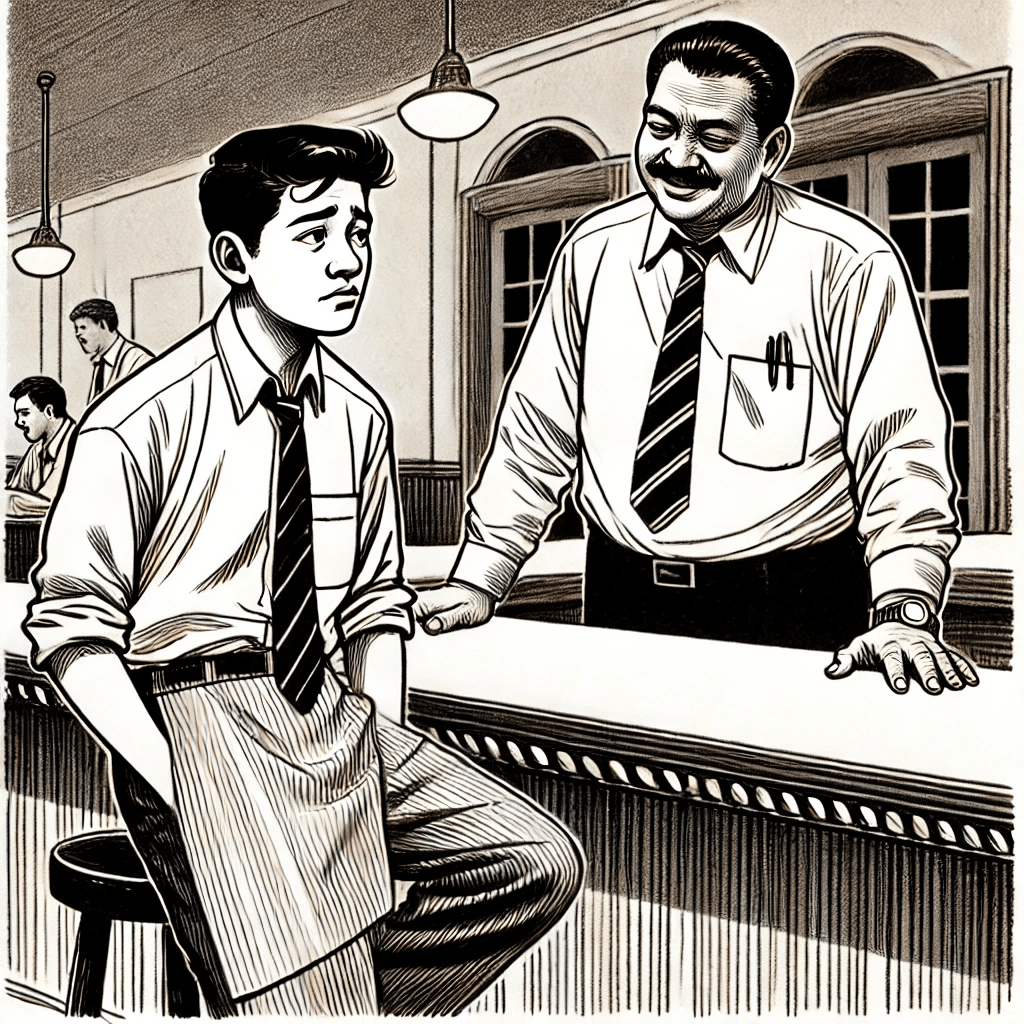

The man motioned for me to sit in an empty chair nearby, and as I sank into it, someone brought me a cup of tea. The warmth of the cup seeped into my hands, and I took it as a sign—perhaps this time, I would be lucky.

After a few moments, the man called me behind the counter. He was dressed in a crisp white shirt, black pants, and polished black shoes—the uniform of someone who held authority. I guessed he must be the manager, maybe even the owner. I introduced myself briefly, the words feeling small in the grandness of this place. He asked what I did back home.

“In Nepal, I worked on a farm. I grew vegetables,” I said, my voice steady. “Both restaurant work and farming require hard work, don’t they?” I added, hoping to prove that I wasn’t afraid of labor, that I could be of use here. But the words of a few Nepalis in the neighborhood echoed in my mind: Whatever you were in Nepal, you left it behind. There’s no point in saying ‘I was this’ or ‘I was that’ back home. Those words hit me hard, a stark reminder of the reality I now faced.

He seemed pleased, a small smile tugging at the corners of his mouth. “Good. Come to work tomorrow, wearing a white shirt, black shoes, and black pants,” he instructed before disappearing back behind the counter. I left the restaurant with a mix of relief and trepidation—the job secured, but the challenge just beginning.

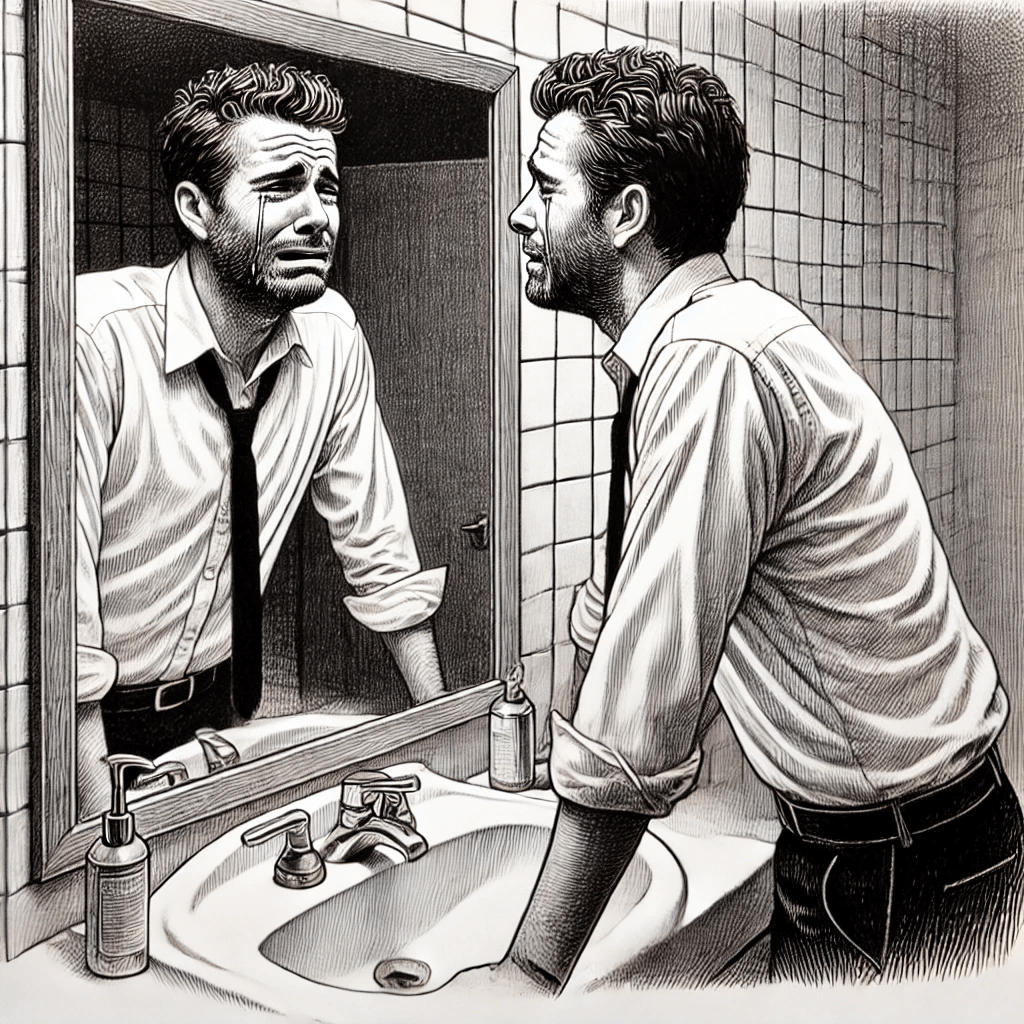

I called Anil, who was waiting for me near the train station on Harvard Avenue. I told him I got the job, expecting some form of congratulations, but instead, he gave me a weary look. “Oh, don’t even ask,” he said when I inquired about his experience working there. “When the work got tough, I went to the bathroom so many times, and I cried looking at myself in the mirror.” The image of him crying in the mirror struck me as absurd, and I laughed out loud, but there was no humor in his eyes.

The next day, I reported to work, feeling the weight of expectations on my shoulders. The restaurant owner had me stand by the counter, watching how others moved with practiced efficiency—taking orders, delivering food, clearing tables, and cleaning up after guests. It all seemed so seamless, but I knew better. Beneath the surface, there was a constant struggle to keep up, to meet the unspoken standards of this new world.

After some time, the owner called me behind the counter again. “This shirt you’re wearing, it’s not white enough. It should be spotless white,” he said, his tone leaving no room for negotiation. I nodded, feeling a sting of embarrassment. “And you should be wearing black shoes too, understand? It looks more professional,” he added.

While he spoke, a waiter brought me an old pair of shoes. “Take off your shoes and wear these,” he said. As I swapped my shoes for the ones provided, I couldn’t help but think of the Nepali belief that you shouldn’t wear someone else’s shoes—perhaps a metaphor for how foreign this new life felt, like stepping into someone else’s path, uncertain if it would fit.

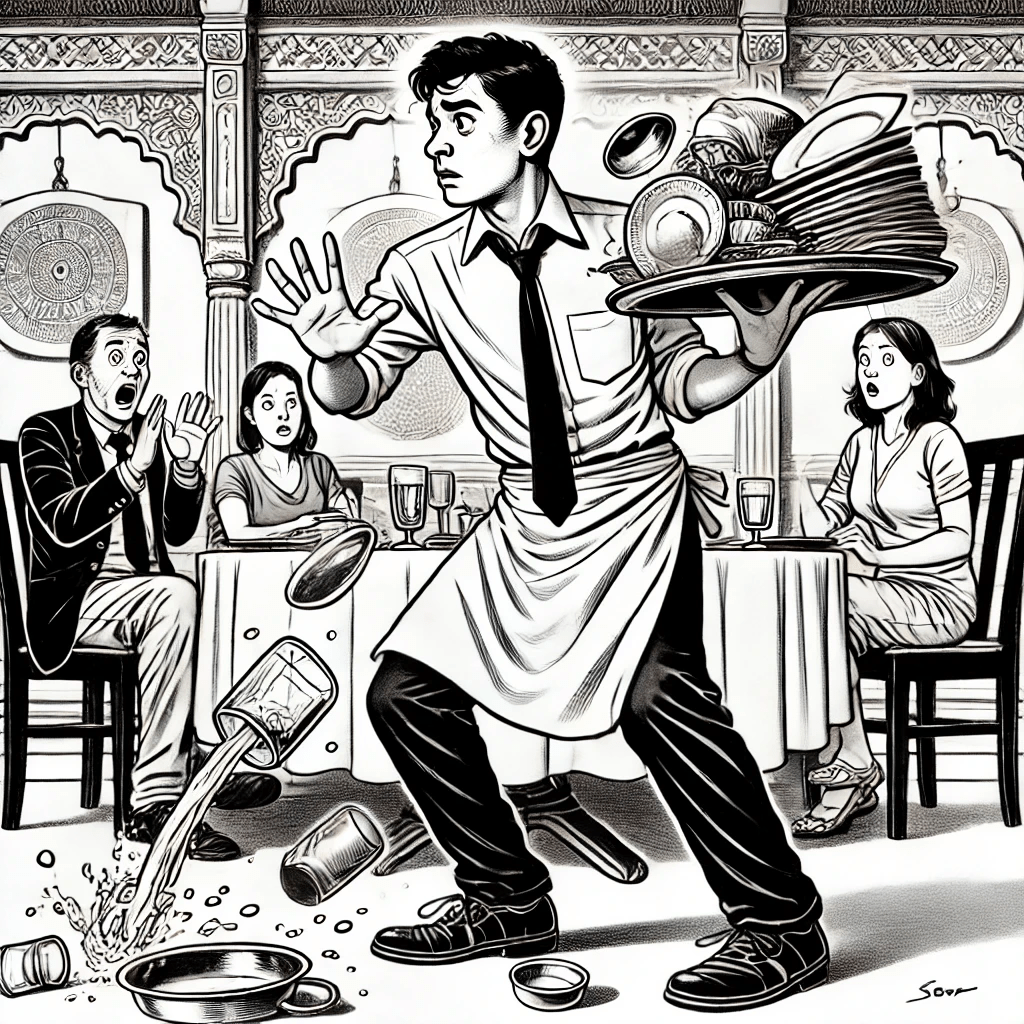

I moved toward the counter, ready to begin my work. A young Bengali waiter, who seemed barely out of his teens, showed me how to arrange the dirty plates and dishes on the tray. I watched him closely, trying to absorb his every move. When he finally walked away, I picked up the tray, feeling the weight of my new responsibilities pressing down on me.

I approached the first table, balancing the tray with care. The restaurant, usually a symphony of clattering dishes and muffled conversations, seemed to fade into the background as I moved to the second table. The tray, a flimsy platform precariously balanced on my palms, felt like a fragile lifeline between success and failure, reminiscent of the delicate task of separating grain from chaff back home.

The first table was easy—just a few plates and glasses, which I managed with a practiced hand. But the second table was different, cluttered with the remnants of a larger meal. The plates and glasses teetered on the edge of chaos. I stacked the four large plates first, feeling the weight press down on my hands. The smaller plates followed, forming a precarious tower, with three empty glasses arranged around them like sentinels. One glass, still half-full of water, sloshed slightly as I adjusted my grip.

I took a breath and lifted the tray, but the balance slipped away. It was as if time slowed down, and I could see the disaster unfolding before it happened. The plates slid first, followed by the glasses, crashing to the floor in a cacophony of shattering porcelain and splintering glass. The sudden noise was a gunshot in the quiet hum of the restaurant, jolting a female customer at a nearby table to scream in surprise.

For a moment, everything froze. Conversations stopped, forks hovered mid-air, and all eyes turned to me. A wave of heat flushed through my body, my face burning with shame. I looked around, the room spinning slightly as the reality of my failure settled in. The restaurant owner was watching me, his expression unreadable, but a slight, almost imperceptible smile tugged at the corners of his mouth. It wasn’t a smile of amusement or kindness—it was the smile of someone who had seen this too many times before, someone who knew that failure was inevitable in this harsh landscape we called America.

Guilt weighed down on me, making my limbs heavy and slow. I stood there, holding the empty tray, paralyzed by indecision. Everything around me blurred, the sharp edges of reality softening into a haze. Not knowing what else to do, I knelt down and began to gather the broken pieces of glass with my bare hands. The sharp edges bit into my skin, but I hardly noticed, too consumed by the need to fix what I had broken.

The manager’s voice cut through the fog in my mind, sharp and commanding, as he shouted at me in Hindi from behind the counter. His words were harsh, filled with the authority of someone who had seen too many immigrants like me stumble and fall. I dropped the shards, realizing how foolish I had been. The Bengali waiter appeared beside me, moving swiftly with a broom and dustpan. He swept up the mess with the efficiency of someone who had long learned the hard lessons of survival in this foreign land.

The next day was no easier. The restaurant was packed, every table occupied, the air thick with the scent of spices and the soft murmur of conversations. The atmosphere felt like a race, each worker moving at a breakneck pace to keep up with the relentless demands of the customers. I was rushing past the counter when the tray I was carrying struck the hanging lights above, sending them swinging wildly. The sharp clanging of the lights echoed through the room, and for a split second, I feared they would shatter just as the plates had the day before. Fortunately, they didn’t, but the sound was enough to draw the attention of the owner.

He approached me, his face inches from mine, and this time, there was no smile. His voice was low, almost a growl, as he warned me, “If you make another mistake like this, I’ll fire you. The cost will be deducted from your paycheck, got it?” His words were a cold reminder that there was no room for error in this unforgiving world. I nodded, my throat tight with the fear of what might come next.

My daily routine at the restaurant began with cleaning the glass near the door and the mirror in the restroom. Each morning, I would wipe away the smudges and fingerprints, the glass gleaming under my efforts. But the reflection in the mirror always brought me back to Anil. I remembered his words, how he had cried while looking at himself in the mirror, and I now understood the weight of those tears—the loneliness of being far from home, in a place where every mistake felt like a step backward.

There was another Nepali working at the restaurant, a quiet man who had been in America longer than I had. Occasionally, he would share his experiences with me, his voice tinged with the wisdom of someone who had witnessed the highs and lows of the immigrant journey. “You can only enjoy working here if you forget what you did or who you were in Nepal,” he once said, his tone resigned. “People say life starts from zero in America, but in my opinion, life here starts from minus.”

His words puzzled me at first, but as he explained, they began to make sense. “Honestly,” he continued, “if you have to forget everything you knew before, isn’t life starting from minus?” It was a sobering thought—the realization that the American dream wasn’t just about starting over; it was about erasing the past, about becoming someone new in a place that demanded everything from you, even your memories.

The Bengali waiter, despite his young age, was a mix of laziness and cunning. He spoke broken English, just enough to get by, but his real skill lay in his ability to shift the burden of work onto others. We often clashed, his commands in Hindi grating on my nerves as he ordered me to clean tables or fetch items from downstairs. But when an American customer asked him something he didn’t understand, he would quickly pass the responsibility to me, his tone suddenly meek and deferential.

His work ethic was questionable at best. During busy times, he would disappear into the toilet, only emerging when the hard work was done. At 11 PM, when we were supposed to clean the floors, he would sit down to eat, ignoring the tasks that still needed to be completed. “Lazy,” I would mutter under my breath, my frustration simmering beneath the surface.

Yet, there were moments when his behavior softened. After work, as we walked along the cold, dark streets, he would call out to me, offering a cigarette or a fruit drink he had taken from the restaurant. These small gestures of kindness, though rare, were a reminder that we were both struggling in our own ways, both trying to find a foothold in a world that often felt indifferent to our efforts.

One night, as we were preparing to leave, the restaurant manager stopped the Bengali waiter in his tracks. He demanded to see the contents of his bag, and one by one, he pulled out cups of yogurt, gulab jamun, kulfi, and lemonade, laying them out on the table for all to see. The sight was humiliating, a public shaming that left the young waiter frozen in place, his guilt on display for everyone in the restaurant. He looked around, his eyes wide with shame and fear, and then, overwhelmed by the weight of his actions, he burst into tears, his sobs echoing in the quiet room.

From that day on, he never ordered me around in front of others. His silence reflected the understanding we had come to—an unspoken agreement that in this foreign land, we were all trying to survive, each of us stumbling and learning as we went.

This excerpt is from the memoir I started writing in 2013, the year I journeyed from Nepal to the United States. What began with a clear endpoint in mind has evolved into an ever-unfolding story, with new chapters added every three months.